1987

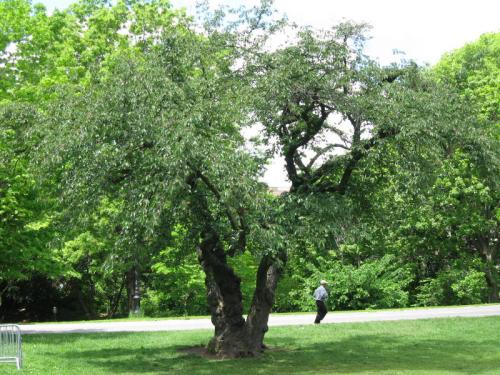

I met Gondim in Rio de Janeiro in 1987. He brought me to Morro dos Prazeres, a favela whose name translates into English as “Hill of Pleasures.” We took the streetcar from downtown up to the neighborhood of Santa Teresa, climbing a couple thousand feet along the way. It was (and still is) Rio’s last streetcar line, and the trip is a step back in time. At the end of the line, you arrive in Santa Teresa’s walled streets and tight alleys, a Bohemian retreat high above the Rio’s noise and splatter. It’s a nice place, and the mountain air is cool.

One turn and a hundred feet down another street, Santa Teresa gives way to small houses climbing up the hillside in seemingly ramshackle fashion, stacked one atop the other to the sky. Children play on rooftops, their kites hanging in the ocean breeze. The two neighborhoods cling to each other on the steep hillsides of Rio de Janeiro in an uneasy relationship marked by occasional hostility, outbreaks of violence, and cheap domestic help. The views are breathtaking across the Guanabara Bay. Back in 1987, Gondim introduced me to Walter, the “professor,” a fan of Fidel Castro’s and leader of the neighborhood association in Morro dos Prazeres. I spent time there talking to people, hanging out, following Walter around.

At that time, Gondim lived in Santa Teresa, among artists and musicians and dancers. It was love and revolution all night long over cachaça, weed, and samba. At night, and sometimes during the day, I played music anywhere I could, with Rogerio or for the girls on Avenida Atlântica between tricks, the ocean crashing across the road beneath the moon and the Southern Cross.

1992

Five years passed and I wasn’t a very good correspondent. Neither was Gondim or Rogerio or anyone in Rio. In 1992, I found Rogerio in Flamengo, the neighborhood down on the beach below Santa Teresa. He asked me what I was doing, and I told him I was on my way to Belém. Belém!, he screamed—there are only crooks and thieves and whores there! Madness to go there! he told me. My people, I thought, and then he gave me his sister’s phone number and said I should look up her up when I get there. Next I went to Gondim’s offices at the magazine, but the editor told me he had moved. Where to? I asked. Belém, she said, and she gave me a phone number.

In Belém, it was sweaty nights on the street in Cidade Velha with Gondim and his friends, among them Petit, a Catalan who had married a Belemense girl and become a professor at the university. We drank beer, ate chicken and rice, and sang songs about everything. With Marga (see the Tamba-Tajá stories) I took in the arrival of Iemanjá on the beach at Mosqueiro in 1992. Márcia took me to her neighborhood, Bom Futuro, which like Morro dos Prazeres had a meaning that seemed at odds with its circumstance, “Good Future” in Portuguese. We had great parties at her house and a photograph of all the women in her family, four generations, hangs in my office next to my desk, not far from a photograph of my own mother.

Bom Futuro was an invasão—they didn’t call them favelas in Belém—in a swampy area amid the mega-invasão of Área Cabanagem (pop 200,000) named after Oscar Neimeyer’s nearby monument to the slave and Afro-Native rebellion that occurred in Belém in the 1830s. Chiquinho took me to his invasão in Aurá, a suburb about an hour or 90 minutes from central Belém by bus. I spent years with him and his comrades as they struggled to pave the streets and keep the lights on. I cherished these friends dearly, as I also loved M-J, who became my accomplice in dreams for a few years.

Then things changed.

The details are unimportant. What matters is that things changed because I made decisions that I don’t understand today. The right thing to do now seems so obvious, though it was so obviously the wrong thing to do at the time. My mistake was not so much in doing right or wrong, but in doing either only half way. I forgot my passion at some point, and my calling went to rest beneath a rock of responsibility or reason that did not suit me very well. Maluco Beleza was the song I loved, and it became the life I lived a little by accident and not nearly enough by design.

2008

Years later, when I picked up The Savage Detectives in Brooklyn’s Community Bookstore, I felt like I found something I had lost.

My lives with Greene and Cortázar were there on Bolaño’s pages, in the stories of Arturo Belano, Ulises Lima and their band of poets—the visceral realists—by way of hundreds of small depositions from everyone who had crossed paths with them over four continents and twenty years, chronicling their lovers and affairs, their triumphs and tragedies and madness. About half way through, the literary and historical sweep of the novel becomes staggering, Cortázar resurrected in the granularity of Bolaño’s storytelling and an entire generation of Latin American literature (including at least two Nobel prizes) left in the dust. This was my world.

I laughed out loud on the subway to read Amadeo Salvatierra reminiscing on his hero during the years just after the Mexican Revolution (p. 396),

… I emerged from the swamp of mi general Diego Carvajal’s death or the boiling soup of his memory, an indelible, mysterious soup that’s poised above our fates, it seems to me, like Damocles’ sword or an advertisement for tequila …

And also at the exchange between Belano and Lima and Salvatierra over the one published poem by Cesárea Tinajero, the original visceral realist in the 1920s (p. 421),

Belano or Lima: So why do you say it’s a poem?

Salvatierra: Well, because Cesárea said so … That’s the only reason why, because I had Cesárea’s word for it. If that woman had told me that a piece of her shit wrapped in a shopping bag was a poem I would have believed it …

Belano: How modern.

I felt my heart tug when Joaquín Font spoke about his release from the mental hospital where he’d spent the last several years (p. 400) …

Freedom is like a prime number.

… and when Edith Oster, a heart-broken, ill, displaced Mexican in Barcelona, told of how she went to find a payphone to call her parents in Mexico City (p. 436),

In those days, Arturo and his friends didn’t pay for the international calls they made … They would find some telephone and hook up a few wires and that was it, they had a connection … The rigged telephones were easy to tell by the lines that formed around them, especially at night. The best and worst of Latin America came together in those lines, the old revolutionaries and the rapists, the former political prisoners and the hawkers of junk jewelry.

She had broken Belano’s heart, too, but the image brought me back to Vargas Llosa’s revolutionaries in Historia de Mayta, who sat around debating the finer points of Marxist theory in their garage, perched atop stacks of their party’s newspaper that had no readers and never saw the light of day, much less of a dim bulb or candle for covert reading in a dormitory, prison, or monastery.

Bolaño himself was at one time or another an old revolutionary, a former political prisoner, and a hawker of junk jewelry. Adding rapists to the mix only put down the rose-colored glasses of our generation’s passions and all those fights between Garcia Marquéz and Vargas Llosa as if to say “enough, already.” Yet being Bolaño, it would have been more like a visceral scream from the front row during a book reading at a polite salon or book store.

The Savage Detectives is a fractured narrative told in the shards of pottery and broken mirrors laying about the floors of the places where Bolaño slept. I read Bolaño and I saw what had become my life.

Notes and Credits

The photo of Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives was taken by the author on his nightstand. This is the normal appearance of my end table. I picked up the leather Brazilian street scenes in Salvador, Bahia, in 1993.

Bolaño’s biography is well-noted and I won’t go over it here, except to say that the last 10 years of his tragic life (cut short by terminal illness) was one of those artistic outpourings that will live in legend. In a brief period of time, Bolaño the cast-off cast-away reshaped Latin America an became its voice (for now, at least).

The photo of Santa Teresa and Morro dos Prazeres comes from the Wikimedia Commons and a photographer named “chensiyuan.” The photo of Belém from the Amazon River was taken by the author in 2000, arriving in Belém on a boat trip that began in Manaus about 10 days earlier. The photograph of Bom Futuro was taken in 1995 on a visit to Márcia’s house. I’ve chosen for now to leave out my photos of Márcia, her family, and the parties we had.

The picture of the Bolaño graffiti was taken from gsz’s photostream on Flickr. The photo of the author and Gondim was taken on the beach at Mosqueiro in 1995. Mosqueiro is the old resort area of Belém, still within the city limits but on a remote island, where the elite used to have weekend vilas and houses.

Earlier this year, torrential rains caused flooding in Rio that resulted in a huge landslide in Morro dos Prazeres and other areas. As a result, the mayor of the city developed a plan to remove the neighborhoods, on the pretext that the danger of flooding is no longer tolerable. The problem with this logic, however, is that Rio’s favelas have always had this problem in the annual rainy season. To many, it seems the floods are just an excuse to to solve some of Rio’s other problems with crime and drugs (really a police problem) by blaming the poor and tearing down their neighborhoods.

This is the same issue that drew Janice Perlman to the favelas in the 1960s and me there, later, in the 1980s. Unfortunately, the problem of drugs and organized crime is all too real. In 1987, when I was there, the police routinely went into Morro dos Prazeres and rounded up young men for summary executions – this as a warning to others and a means of controlling the population. Twenty years later, the film Trope de Elite (Elite Squad) chronicled the same story, Morro dos Prazeres still there at the center.

The Memorial da Cabanagem is a landmark in Belém. It was built by Governor Jader Barbalho after he became one of 9 resistance candidates to win election to governorships against the military regime in 1984. The pretext is that Barbalho’s victory signaled a rebellion of Cabanagem-like proportions, the people rising up against the elite. After humble beginnings, Barbalho himself has been governor twice and held seats in both the national congress and the senate, where he was that body’s leader for a short while until he was impeached while rumors and allegations of corruption mounted. Barbalho is one of the richest men in Pará. As with Fernando Collor, time conquers all, and Barbalho is back in the national congress representing Pará. Jeferson Assis’s Flickr photostream has many images of the Cabanagem monument, as does Jeso Carneiro.

Bolaño’s rigged payphones reminds me of stories my friends told about the payphones in Washington Heights in the 1980s. The Latin American drug traffickers (or so my friends said) would rig them to make free international calls, and everyone in the neighborhood used them.

When all is said and done, I wish peace to my friend Gondim and pray that I will see him again.