Note: This is the first of three posts in an extended essay exploring my relationship with my father and my son through the songs of Cat Stevens/Yusuf Islam.

Another Saturday Morning

When I was a child, Saturday mornings were tranquil and unoccupied, a time when no one had work to do or church to attend. It was the one day of the week that mom got to sleep in, and it was the one morning of the week when my father had some time to himself. And so it was that Saturday mornings began with a ritual of discovery, waking up to seek out my father in the family room to see what he was doing. This was important, because whatever it was that he was doing, it looked important.

Sometimes he would be reading; sometimes he would be writing. But he was always writing in all the books he read, and when he listened to music on the stereo, he scribbled all over the record sleeves and lyric sheets. And then sometimes he was just writing in one of his empty books that were simply labeled “Record.” He had a whole bunch of these already filled on the bookshelves.

One Saturday morning, I came into the room and heard a new record, as I often did. This one was “Teaser and the Firecat,” by an oddly-named singer called Cat Stevens. From that day on, the song “Peace Train” became an anthem in our household, for it was in those days, or thereabouts, that my parents and their friends were peace-loving young people, the “social left” of their local Catholic Church, complete with their own bearded-hippie-Jesus priest who rode a motorcycle, preached against war and hosted wonderful weekends at his family’s fishing camp down on Lake Verret. In our household, guns were forbidden, not even toys, and we didn’t go hunting or shooting, all of which set us quite apart in Louisiana. Guns, my father said, had only one purpose, which was to kill people, and that was not something to celebrate.

At the same time, from the walls of our living room—the same living room where Cat Stevens, Bob Dylan and Joan Baez sang every Saturday morning—there hung a striking sunset-silhouette photograph of my father’s tank out on the ground around Fort Hood, Texas, where my brother and I were both born. On the same or a nearby wall (it changed every once in a while) my father’s bayonet was mounted on a felt-covered board with some other mementos, and on another wall hung award my mom got for service to Army wives. Before Cat Stevens, Captain Ronald James Guidry was a tank commander and expert marksman.

Over time, Cat Stevens’ music continued to be played in our house. My father brought home each new album, all the way through Numbers, though I recall thinking that “Bannapple Gas” didn’t do the same thing for me that the other songs did. Within a few years of that, however, around the same time that Cat Stevens seemed to disappear—and I would have no idea why that happened until many years later—my brother and I were both playing the guitar and learning the ubiquitous Cat Stevens’ Greatest Hits songbook cover-to-cover.

It was around that time, too, that the songs started to mean something different to me. They were no longer songs that were important to my father for reasons that he told us. They were songs that helped me think about important things, too. They were songs that captured the way I had begun to feel about my father as I was starting to think about what I wanted from this world and realized, with no small degree of concern, that the things I wanted weren’t what he wanted for me.

This was a challenging idea, because I thought of my aspirations and values and dreams as direct extensions of my father’s. I didn’t understand the difficulty he had with some of my ideas, but I began to think I should worry less about his feelings than just figuring out how to move along. Like every boy my age with a guitar, I sang the words to “Father and Son” as if I had written them myself.

How can I try to explain, when I do he turns away again.

It’s always been the same, same old story.

From the moment I could talk, I was ordered to listen.

Now there’s a way, and I know that I have to go away.

I know I have to go.

Cat Stevens, “Father and Son,” 1970

For his part, I recalled how my father listened to “Oh, Very Young,” seeing in his eyes the familiar look of loss that increasingly haunted his moods the older he got. I couldn’t tell if he was mourning his own lost youth or mine, or perhaps the notion of lost innocence, though whether personally or in general I couldn’t quite tell.

Oh very young what will you leave us this time?

You’re only dancing on this earth for a short while

And though your dreams may toss and turn you now

They will vanish away like your daddy’s best jeans

Denim Blue fading up to the sky.

And though you want him to last forever

You know he never will.

Cat Stevens, “Oh, Very Young,” 1974

What I can say is that to this day, almost 40 years after first hearing that lyric, I cannot see my father in blue jeans without hearing the song in my head. The images are burned in my mind and branded on my heart, stirring me still as I grow older and watch my own son as he emerges from the fog of childhood into a person of his own substance and mettle.

Notes and Credits

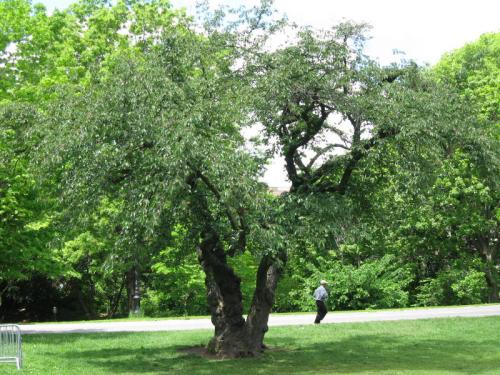

On some Saturday mornings, my father took my brother and me to Audubon Park. These were especially magical. He would sit in the grass and paint watercolors while we played. Then he took us around the park, across the bridges and next to the lagoon. He pointed out the places where he and my mother fell in love. Whatever he did on those Saturday mornings, my brother and I followed.

When challenged that guns could be used to kill animals for food, my father simply pointed out that guns were not used to kill the animals we ate. He’d spent a goodly part of his childhood on his grandparents’ farm in Lutcher, Louisiana, fifty or sixty miles up-river from New Orleans. It was part of the sugar plantation there, but now it’s a Kaiser Aluminum Plant. And as a teenager, he was a butcher in his neighborhood meat shop. He knew how animals became food, and the few shot with guns today had mostly been killed in other ways for most all of human history. When pressed on the point, he explained military history and why we have guns. He was adamant about this.