The truth is that money is often a divisive influence in our lives. We keep our bank balances secret because we worry that being candid about our finances will expose us to judgment or ridicule—or worse, to accusations of greed or immorality. And this worry is not unfounded.

Jenny Offill and Elissa Schappell, Money Changes Everything (New York: Doubleday, 2007), p. xi

Brooklyn Reading Works:

The Truth and Money

On April 15, 2010, the Brooklyn Reading Works will present its monthly writers’ program on “tax day.” This happy accident, observed last summer in a casual conversation over coffee with Louise Crawford, resulted in the idea for a panel called “The Truth and Money,” a reading and Q & A with three authors whose work has taken on money in some significant way.

Our three panelists are:

Elissa Schappell, a Park Slope writer, the editor of “Hot Type” (the books column) for Vanity Fair, and Editor-at-large of the literary magazine Tin House. With Jenny Offill, Schappell edited Money Changes Everything, in which twenty-two writers reflect on the troublesome and joyful things that go along with acquiring, having, spending, and lacking money.

Jennifer Michael Hecht, a best-selling writer and poet whose work crosses fields of history, philosophy, and religious studies. In The Happiness Myth, she looks at what’s not making us happy today, why we thought it would, and what these things really do for us instead. Money—like so many things, it turns out—solves one problem only to beget others, to the extent that we spend a great deal of money today trying to replace the things that, in Hecht’s formulation, “money stole from us.”

Jason Kersten, a Park Slope writer who lives 200 feet from our venue and whose award-winning journalism has appeared in Rolling Stone, Men’s Journal, and Maxim. In The Art of Making Money, Kersten traces the riveting, rollicking, roller coaster journey of a young man from Chicago who escaped poverty, for a while at least, after being apprenticed into counterfeiting by an Old World Master.

Please join us for the event at 8:00 p.m. on Thursday, April 15, 2010, at the Old Stone House in Washington Park, which is located on 5th Avenue in Park Slope, between 3rd and 4th Streets, behind the playground.

Read about all the Brooklyn Reading Works events at Only the Blog Knows Brooklyn and the BRW website. For info on the Old Stone House and its role in the Battle of Brooklyn (1776) and contemporary life in Park Slope, go here.

Many thanks from all of us at Truth and Rocket Science to Louise Crawford, of Only the Blog Knows Brooklyn, for making this possible.

Money, It’s a Gas

The subtitle on the cover of Elissa Schappell’s book says everything you need to know about the stories within: Twenty-two writers tackle the last taboo with tales of sudden windfalls, staggering debts, and other surprising turns of fortune. “The last taboo” is how Schappell and her co-editor, Jenny Offill, characterize our behavior when it comes to money, because nobody really wants to talk about it.

People are secretive and embarrassed—for having too little, or too much, or something to hide about the reasons either way. In a country where everyone seems to have a story of how they, or their parents or grandparents, used to be poor, any personal narrative but “hard work” is out of the question. Even hardened criminals revel in detailing the blood, sweat, and tears that go into their “work.” No one, it seems, can sit back and say with no embellishment or apology, “I got lucky, that’s all.” Money is the measure of what we deserve, and in our society what we deserve is in some sense who we are.

In The Happiness Myth, Jennifer Michael Hecht seeks to disentangle why things that are supposed to make us happy frequently don’t. To the notion that “money doesn’t buy happiness,” she shows that it does, to an extent. For most of human history (and pre-history), people have lived in conditions of terrible, frightening, life-threatening scarcity that money in no small part has eradicated for all but a very small fraction of Americans. (In line with Schappell’s notion of money-taboo, I now feel the urge to apologize and state something statistical about hardship and inequality in America, but I won’t. We deserve ourselves and all of our money issues.) Hecht writes,

“We need to remember that most people through history have been racked by work that was bloody-knuckled drudgery, the periodic desperate hunger of their children, and for all but the wealthiest, the additional threat of violent animals. Nowadays a lot of what we use money for is a symbolic acting-out of these triumphs.”

Once out of poverty, in other words, what we do with money—or more precisely the things we feel when using money—have a lot to do with ancient urges and inner conflicts that endure in our minds, bodies, and culture across time and without, so it seems, our self-conscious awareness of them. Money does buy happiness, up to the point we’re out of poverty, and then the real problems begin.

Like the craving for fat and things that are sweet, the urges we satisfy with money are deeply embedded in our being, fundamental to the way we evolved in the most far-away places and times. It’s all fine and easy to understand or forgive, but we all know what happens when you eat too many doughnuts.

Doughnuts to Dollars

Yet money is not like a doughnut. This we all know—money isn’t some thing, it’s just some non-thing you use to get doughnuts or whatever else you think you need. The economists’ word for this quality is fungible. Adam Smith introduced money in his great book on wealth by reviewing the things that societies have used for exchange measures over time, including cattle, sheep, salt, shells, leather hides, dried codfish, tobacco, sugar, and even “nails” in a village in Scotland that Smith knew of. All this was terribly inconvenient, and Smith noted that the use of precious metal as a stand-in for things of value constituted a considerable advance—

“If, on the contrary, instead of sheep or oxen, he had metals to give in exchange for it, he could easily proportion the quantity of the metal to the precise quantity of the commodity which he had immediate occasion for.”

Money in this sense becomes nothing but a means of measurement, and it would be perfect indeed if money’s effects on the world ended there, but we all know that they don’t.

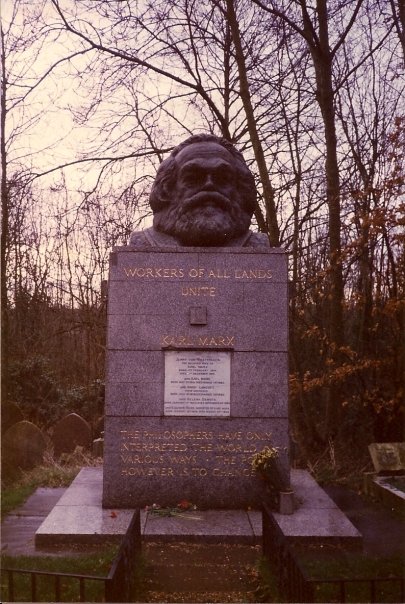

Money—as Elissa Schappell and Jenny Offill, Cyndi Lauper and conventional wisdom tell us—changes everything. Money’s magical qualities go well beyond simple notions like greed. Money’s powers are existential, transformative, and really weird. Money makes us into things we are not. Karl Marx was pretty blunt about this—

“Money’s properties are my properties and essential powers … what I am and am capable of is by no means determined by my individuality. I am ugly, but I can buy for myself the most beautiful of women. Therefore I am not ugly, for the effect of ugliness—its deterrent power—is nullified by money. I, in my character as an individual, am lame, but money furnishes me with twenty-four feet. Therefore I am not lame. I am bad, dishonest, unscrupulous, stupid; but money is honored, and therefore so is its possessor. Money is the supreme good, therefore its possessor is good. Money, besides, saves me the trouble of being dishonest: I am therefore presumed honest. I am stupid, but money is the real mind of all things and how then should its possessor be stupid?”

Marx may have fallen short as an economist, but then again so do most official economists. In terms of money’s most basic ontological properties, however, it’s worth noting that he got money right.

The Glow

In the story of master counterfeiter Art Williams, Jason Kersten tells one such story of how money changes people, their values, and the truths that bind them together. Art’s counterfeit was of an extraordinarily high quality, and its effect on people was fascinating to behold. Art called it The Glow—“They would get this look on their face … a look of wonder, almost like they were on drugs. It was like they were imagining the possibilities of what it could do for them, and they wanted more.”

Like the anonymous subjects of history in Hecht’s writing (note: that’s us), Art wanted something that money, or the lack of it, had apparently stolen from his life. Art’s “pursuit had very little to do with money, and the roots of his downfall lay in something impossible to replicate or put a value on. As he would say himself, ‘I never got caught because of money. I got caught because of love.’”

So where does money get us? It’s easy to tell stories of money and doom, but we all know that without enough of it we’d be unable to do anything we need to do, let alone the supposedly unnecessary things that seem to make up for the drudgery of a life built upon doing the things we need to do. Is the grubbiness of money as it comes off in the Pink Floyd song all there is to it? Or is there more?

Join us on April 15, after affirming the give-away of twenty-eight percent (for most of us) of your annual harvest.

Questions: jguidry.7@gmail.com or 212.729.7209.

Credits and Notes

Many thanks to Louise Crawford for inviting me to curate the Tax Day BRW panel, through the Truth and Rocket Science blog. A sincere debt of gratitude, not to mention late fees, is owed to the Brooklyn Public Library, for enabling my research and inquiry into this topic. The BPL’s copies are indeed those photographed on my dining room table to lead the blog post.

Jenny Offill and Elissa Schappell, Money Changes Everything (New York: Doubleday, 2007).

Jennifer Michael Hecht, The Happiness Myth (New York: Harper One, 2007), p. 129.

Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, in Robert L. Heilbroner, ed., The Essential Adam Smith (New York: W. W. Norton, 1986), p. 173.

Karl Marx, Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, in Robert C. Tucker, editor, The Marx-Engels Reader, 2nd ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1978), p. 103.

Jason Kersten, The Art of Making Money (New York: Gotham Books, 2009), p. 152 (first quotation) and p. 4 (second quotation).

Photo Karl Marx’s grave, Highgate Cemetary, London, taken by the author in January, 1994, while on layover on the way to South Africa and its historical elections later that year.