There are jobs, and then there are jobs.

We built our world on petroleum, especially in the state I come from, Louisiana. We power our cars and computers and houses with petrol and its funky little brother, natural gas. Over the course of the long twentieth century, the automobile fueled explosive growth in the American economy and allowed people to spread out in endless suburbs that offered relief and tranquility compared with the noise and chaos of urban life.

Along the Gulf Coast and elsewhere, countless thousands of jobs are devoted to the exploration, drilling, refining, distributing, selling, purchasing, and using of petrol in its many forms. We create our food with petrochemical fertilizers that rely on the abundant natural gas deposits found deep in the Gulf of Mexico along with oil. The plastic bags we carry our food in are made of petroleum. Cosmetics and personal lubricants are made of petrol.

Oil and other fossil fuels have made everything we know possible, from the things we use to the lifestyle of abundance that for some seems an American birthright. We Americans are the people of the tar.

We eat the oil, and the oil eats us

Back in the 1970s, when gas prices shot through the roof because of the Arab Oil Embargo, the rest of the country went into a tailspin while Louisiana thrived on oil. The construction of the New Orleans Superdome, opened in 1975, started a downtown building boom in New Orleans that reshaped the city before my eyes as I grew up. Then in the early 1980s, when oil prices fell as the country’s economy recovered, New Orleans and Louisiana went into a tailspin. The oil companies moved their offices to Houston and drilling shut down as oil fell below $15 a barrel, the price at which it was no longer economical to produce oil in Louisiana. As the oil money left, people lost jobs all over the state and everyone suffered.

Now, as the Deepwater Horizon blowout has become the world’s worst man-made environmental disaster, Americans face an impasse. Do we follow Louisiana’s own politicians and call for more drilling? These are the same politicians who along with other (mainly Republican) politicians around the country created an environment of contempt for business regulation that fueled a lawless world in the boardroom, on the factory floor, and in the marshes and mountains and wildlife prerserves. Corporate lobbyists wrote environmental and workplace protection laws. Our social world—our values and the values reflected by our government—made it the casual business of the day to celebrate the sub-prime mortgage market, overlook safety in coal mines, and build drilling rigs without proper blowout protection. It was the time of our life and there wasn’t an American alive—left, right, or independent—who didn’t just love their IRAs, home equity, air conditioning, and cheap gas.

Un-natural disasters

Deepwater Horizon comes almost 5 years after the “natural” disaster of Hurricane Katrina, which continues to show us what can happen when the government abandons its people. The Katrina disaster was neither inevitable nor natural. It was a man-made disaster of the first degree, founded upon the same neglect and abdication of social responsibility that are at the core of America’s post-Reagan social contract.

Deepwater Horizon comes almost 5 years after the “natural” disaster of Hurricane Katrina, which continues to show us what can happen when the government abandons its people. The Katrina disaster was neither inevitable nor natural. It was a man-made disaster of the first degree, founded upon the same neglect and abdication of social responsibility that are at the core of America’s post-Reagan social contract.

Our world will change as the oil runs out, which it will do one day, sooner rather than later by current predictions. How many disasters do we need to learn that all of us are made better by a government that provides social protections and guarantees against exploitation—of people, environments, and resources? The BP oil disaster is our opportunity now for the national courage to get off oil. Such a matter of fundamental change could be achieved only by a massive state-led effort akin to the New Deal.

For comparison’s sake, here’s The Deal We Got: oil will kill us, either way. It’s already started. If it doesn’t kill us now, it will kill our children or grandchildren. There’s no going back now on the damage oil has done and will do to Louisiana and the Gulf Coast at large. Add one hurricane to it this year and it’s over.

Imagine

Can we just think about ending oil? It doesn’t matter how realistic it seems. It will hurt. It hurts to stop any self-destructive addiction. Yet while it’s going to hurt one way or another, it doesn’t hurt to dream a little. Ask any hurting person. Or these pelicans. Why not …

… deploy the government’s resources to bail out the regular people of Louisiana who will lose their jobs in this tragedy? If it’s good enough for Goldman Sachs it’s good enough for the Bayou State.

… put the Army Corps of Engineers to work creating a levee system that channels the immense force of the Mississippi River to the restoration of the coast? The same government agency that corralled the river in the first place ought to be able to set it free. Indeed, by cutting off the annual flood, the levees have helped erode the Louisiana wetlands at the rate of one acre per hour. Restoring the annual flood just might be the best way to combat the effects of the oil spill.

… cut our addiction to automobiles and airplanes by building railways—high speed and local—that can rely on wind, hydro, and other safer energy sources? Start with rails in Louisiana so that people there don’t have to buy gas and can still get to work. Put these guys to work at home and let them become a corps of railroad builders who can teach the rest of the nation how it’s done.

Imagine a permanent, federally funded project of restoring and then maintaining one of the world’s most vital and richest wetlands. Call it real conservation and tip your hat to Teddy Roosevelt (the ex-Republican Bull Moose). The point is that this is not just an oil spill. It’s the big one, the wake-up call. If the fear of losing jobs is what keeps people in Louisiana under the thumb of big oil, then let’s find them other jobs. Are we slaves?

This isn’t rocket science. It’s a matter of will. We are the richest country on Earth, and we can do this if we want to. While we’re at it, we can finally clean up the mess and set things to right from Katrina. What America does shows the world—and more importantly, ourselves—what we really want and what we really care about. What shall we do this time?

The glass

The glass is a champagne flute from Williams Sonoma. I photographed it on the southern edge of the pond in Prospect Park, Brooklyn. The pond is home to a lot of turtles. Fish are stocked and then fished out by the people who live in the neighborhood. Macy’s sponsors an annual fishing tournament in the park. Swans, geese, ducks and other birds make the pond home, for at least part of the year. Of late, there has been a series of mysterious animal deaths in the park, prompting outrage and concern by folks all over the city. Comprehensive coverage of what started with an injury to John Boy the Swan, which later resulted in his death, can be found in Gothamist and in the Brooklyn Paper. Video of John Boy can be found here.

Notes and Credits

All photographs are by the author, unless otherwise noted.

On the petrochemical sources of our food, no one has written more eloquently than Michael Pollan. In his book, Omnivore’s Dilemma, he provides an accounting of the carbon footprint beneath the food we buy so cheaply in the supermarket, as well as the government policies that prop up the union of agribusiness and petroleum.

The sub-title, “We eat the oil and the oil eats us,” paraphrases the title of June Nash’s classic book about Bolivian tin miners, We Eat the Mines and the Mines Eat Us. The book’s title comes from the way the miners talked about their relationship to the mines, mining, the mountains, and the tin companies that exploited them so ruthlessly. Louisiana is like that, a place being eaten up by big companies who could care less about the local people apart from their willingness to work for low wages without union representation. When I was a kid, we sometimes called New Orleans “The Tegucigalpa of the North.” It was sort of joke, just sort of.

On levees and their importance—I grew up about a half mile from the levee. I used to play behind the levee every day in the batture, the swampy land between the levee and the river itself. We played army and pirates behind the levee when we were little. Then we smoked pot and made out. When I was in college at Loyola University in New Orleans, I used to ride my bike from home (commuter student) to the college on the levee. I wrote one of my best songs, “Down By the River,” about falling in love with a brown-eyed girl who gave me my first kiss on the levee. It’s a bluegrass tune.

I took the satellite image of Hurricane Katrina from weather.com a few days before it made landfall. I was holed up in Dallas, Texas, at my mother-in-law’s. I happened to be there visiting, for reasons that had nothing at all to do with the storm. My parents went to my brother’s place in Nacogdoches, Texas—now they were storm refugees and only went home at the end of October, after 2 months in Texas. I kept that image of Katrina. In my anger over the storm and the abandonment of New Orleans, I made it the wallpaper of my computer desktop, not changing it for a couple of years.

The battered house is where my father grew up in the 1940s and 50s. It was on the corner of Lafaye and Frankfort Streets, which was in a new subdivision being made up near the shore of Lake Ponchatrain, where the Air Force had major installations during World War II. My grandparents moved there after the war, once my grandfather— “Grumpy” as we called him—got home from the Pacific and took a job with the Postal Service, where he would work until his retirement. I remember that house in the 1960s and early 70s. I was all of 5 and everything was happy there. Grumpy made ice cream in the back yard and told us funny stories. He let us grandkids take a turn or two each on the hand-crank. It was good ice cream. The house is no longer there.

Environmental Impact Statement

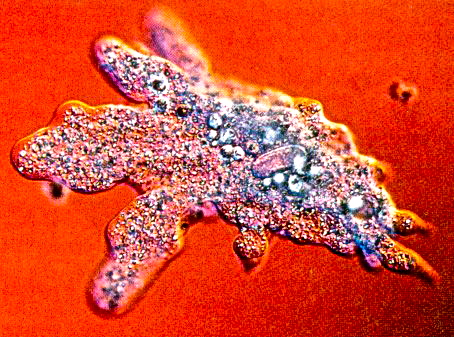

None of the fish, turtles, geese, ducks, or swans that call Prospect Park home were endangered in any way by this photo shoot. In place of oil, I used all-natural, unsulphered molasses, which has the look of oil but is quite sticky and tastes much better.

Molasses is a rather suitable substitute for oil in other ways as well, since it’s a Louisiana product that probably does much less damage than oil. My grandparents grew up on sugar plantations up the river from New Orleans. Grumpy used to tell us how they refined sugar from cane, every single step, including molasses. He knew sugar. Granny used molasses to sweeten the pecan pies she made every year with the nuts she gathered from the tree in her own backyard. Molasses has been around for a long time without causing the epidemic of obesity that can be traced to high fructose corn syrup, which in turn can be traced be to the agricultural policies of the Nixon administration (will we ever run out Republicans in this story?), which in turn can be traced to petrochemical fertlizers and in the end: oil, oil, oil.

The use of the first-person, plural possessive—we—in this essay is intentional. We all own the oil spill. The politicians who created the culture of disregard for public safety and environmental sustainability in business and corporate life are there because they received enough votes to win office. The people who voted them in office did so for various reasons that Thomas Frank documents pretty well in What’s the Matter with Kansas and which for Louisiana are intricately related to the famed “Southern Strategy” that the Republican party adopted with Richard Nixon’s successful presidential campaign in 1968. The race politics that underlay all of this are a tangled (yet quite simple) web that deserve another essay in their own right. This is how America is, for whatever it’s worth. Those of us who didn’t vote for these politicians, we’re also complicit. We use the energy that comes from petrol. We might want to laugh at Sarah Palin’s convoluted explanation of how environmentalists are really responsible for the Deepwater Horizon tragedy, but it’s our culture and we’ll keep driving to work every day, even if on a bus powered by gasoline or its funky little brother, “natural” gas.

We are the people of the tar.