Nego and his little brother outside the family’s house in Moju. This the final installment of Tamba-Tajá, the story of a trip to rural Amazonia in 1993. Double-click the photos to see them in original size.

______________________________________________________

We ate our fill at Nego’s uncle’s place. It was nice, after a long morning of travelling on a hangover. We had a lot of things to carry, bags of food and drinks, some clothes, and things from the city that Aluízio brought for the people we’d see on the way. All fed, we started down the path single file, away from the road, the little house, the clearing, and into the woods. We were carrying a lot, but behind us we left some sacks of food and other things – we’d be back to get them.

The family farm was a couple more kilometers through the woods. The trees were tall and lush and green. Leaves littered the forest floor off the path, which began to turn and then turn back again, as if cutting back to go up a steep hill or mountain, only the land was flat. Flat and densely covered with trees and shrubs.

After a good bit of walking, we came to a creek – igarapé – that had cut a gorge about 6 feet deep and maybe 20 feet across. It wasn’t terribly deep, but it was enough to slow us down a bit. Another 20 or 30 minutes and we arrived at the house, which was surrounded by fruit trees of all sorts. Huge limes hung from one, and we’d use those limes later to bathe in the igarapé behind the house. The house was shingled on one side, straight boards on another, with windows open to the air and what seemed like a lot of space as we approached. You could see through the spaces between the boards. There was no electricity. The water came from a well drawn by a hand crank, up to a thousand-liter tank 10 meters up atop a scaffold. PVC piping brought the water down from the tank and into the house.

On the other side of the path, in front of the house, there were fields of manioc and pepper plants. Pepper was supposed to the salvation of Amazonian smallholders, a marketable crop easy to grow in the climate and soil conditions. Some folks made money on it, but few were truly saved.

The women settled into the house. They wiped the dust from the tables and chairs. They opened the hammocks we would sleep in and hung them from the house’s frame. They began cooking. The man who took care of the place while the family was in Belém came round with the horse, and we took the charrette back to the road to fetch sacks of food and other things needed for the next few days.

Later, I went off with the men into the forest. Aluízio wanted to show me his Amazonia. We brought a bottle of cachaça (ka-SHA-sa), a clear, potent cane liquor, and we walked along pulling cajú from the trees. The cajú grows as a fruity, pulpy bulb with a nut, the cashew, hanging from its end. After a slug of cachaça, you suck on the juice from the cajú to dissipate the burning sensation of alcohol on your tongue. We did this for an hour, stopping from time to time for Aluízio to show me the plants near the ground and explain each one’s medicinal purpose.

After a bit, we reached the virgin rainforest. The trees were as large around as any I’d ever seen, taking three or four men to encircle a trunk, hand to hand. They grew high in their struggle for sunlight, competing with each other as they threw up ever larger leaves, leaving very little light to filter down to the forest floor, were it was damp and cool. In the forest, you feel a chill even as you sweat under the leaves.

Vines hung everywhere and swayed with the gentle breeze that ran through the trees. Bird sounds came from every direction, a dense concert in the round of cackling and crowing, the flapping of wings and stirring of leaves. Echoing caws of differing pitch and resonance shot through the distance from near and far. This was the sound of the forest breathing.

We took a twisted path through the woods and then headed back to more settled places. We stopped to visit neighbors who lived further from the beaten path, in houses of wattled clay daubed onto wood frames made of sapling branches and topped with palm fronds. The clay dried hard as bricks, but I thought it must take a beating in the rain.

One man was making birdcages from reeds and bamboo, fine little pieces fitted together. He caught forest birds and sold them to another man, who took the birds in their hand-made cages to Belém, where he sold them to another man, who in turn sold them on the streets of the city to visitors and local people alike. Of the three men involved, the one in the middle made the most money.

The farmers were talking about the price of pepper and whether or not they’d make any money this year. Then the conversation turned to the price of lumber, and Aluízio asked one farmer if he was going to cut the madeira nobre – the valuable wood, like mahogany – on his land. Some of it might wind up going into beautiful headboards and armoires for sale at specialty importers in Chicago. Some would wind up as yet another wall for yet another room on yet another house in Jurunas.

Back at the farm, darkness began to close in as the women put out the food for dinner. Beans with chicken and meat, rice, fruit, bread, crackers, coffee and farinha, the raw manioc flour grown right there. We mixed the farinha into everything. Farinha de manioc isn’t much to speak of in taste or nutrition, but it stretches the food on your plate and lets you “fool the stomach” into thinking you’ve eaten much more than you have. It tastes good with the beans and brings a crunchy texture to the soupy froth.

By dark, the house was lit with a couple of kerosene lamps not larger than Bunsen burners. A soft light, it brought out the curves and contrasts in everyone’s faces as we talked about life, the weather, the family. OOOOOO-go!, the boy’s mother rang out time and again as the he ran about making noise, upsetting things carefully stowed and stacked and, in general, being a boy. Nego took out his guitar, and we all went outside to sit under the trees and sing. Nego played. His brother played. I played. We shared our stories and ideas and adventures.

Between songs and laughter, the forest told its own stories as the birds calmed and other noises came. Nego told of the time he spent a week at the house by himself. The forest noises scared him so much he would never do it again. Aluízio told older stories about jaguars and snakes and mythical creatures who came out of the forest at night and are sometimes men in appearance. Legend had it that the boto, the pink freshwater dolphin found in the Amazon, would turn into a tall white man in a white hat and white suit, showing up at the village dance to sweep a young girl off her feet and take her back to the enchanted city under the river, where the boto made her his queen.

We became tired and went inside. I crawled into my hammock and pulled up the sheet under a chill. I listened to the night forest and fell asleep to the sounds of snoring and swaying hammocks.

Notes and Credits

The photos for this installment of Tamba-Tajá are all from my 1993 trips to the farm with Nego, except for the photo of the cajú, which is from Wikipedia Commons. The Tamba-Tajá closed by 1995. Nego got married and moved to a small town in the interior of Pará, a town much like Moju, where he became a school teacher – music of course. The small town life in Amazônia is what suited him, so I imagined he was, and still is, happy there.

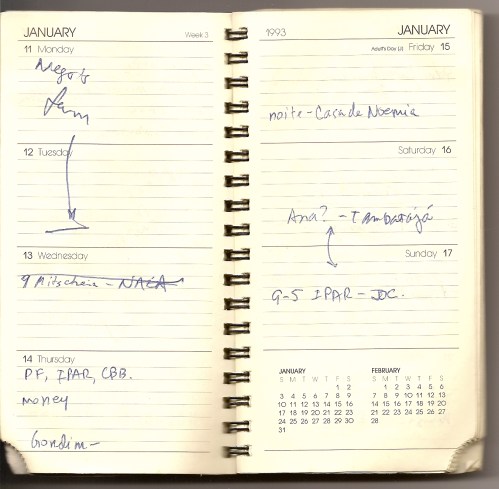

Writing this post has taken me on an interesting journey through my old photos and Brazilian research material, in search of journals and photographs, things to help jog my memory about certain events. I know I have a journal entry somewhere on this trip, but I can’t find it. It’s probably on an old 3.5″ floppy disk somewhere in a box under my son’s bed. I looked through those boxes just now. Among other things, I found the daily calendar I kept in 1993, showing the dates of the trip recounted in this story: I arrived at the Tamba-Tajá around 10 p.m. on Friday, January 8 and came back on Tuesday, January 12. It was the first of a couple more trips, including Holy Week and Easter, April 8-11. One day I will find the journal entries and figure out how well my memory has recounted these events so many years later.

The land issues encountered by the smallholders who Aluízio talked with in this story are quite difficult. I deleted a couple paragraphs from an earlier version of the story that got into those issues; they didn’t work for the story I wrote. But they are real. The further south you go from Belém, the more dangerous it gets, southern Pará being rife with more land conflict than any other place in Brazil during the 1990s. Church people and unionists tried to organize the small farmers and ranch hands, but they were constantly harassed by the big farmers and their henchmen, who as often as not were also the local police.

A good up-to-date article on land issues in Amazônia appears here, by Paulo Cabral for the BBC. The murder of Sr. Dorothy Stang, of the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur, an international Catholic religious order that works for social justice and human rights, was a major issue in Brazil and internationally. A lot more could be written and said about these issues, and I’m working on writing something that was inspired by Rosa Marga Rothe and the Book of Daniel. Coming soon …

For now, I’d like to leave this story with a photo I took of Rosa Marga and Iza that I took in 1998, not too long before Iza passed away. They started this story, and so they should end it.

Wow… Looks amazing. Makes me want to visit. Thanks for sharing 🙂

This really was an incredible tale, an incredible time. You write so well. I really enjoyed it.