In the first installment of The truth and change, I wrote about how the Enlightenment gave us a new kind of science and social discourse that pictured a perfectible mankind, which would be the basis of real democracy and freedom in the future. Yet it was really a Greek tragedy.

Jefferson snubbed the ancients by declaring that there will be something new under the sun, and a hundred years later the world embarked on a century that would witness versions of apocalypse previously imaginable only in epics and divine texts. Everything that the Enlightenment made it possible to imagine, it also made it possible to destroy. That was the dilemma of my generation . . .

Technoredemption Goes Pro

The 1933 Chicago World’s Fair gave us the “House of Tomorrow,” which still stands in Indiana and at 78 years old combines the future and past in one space. Like most dream houses created since the 1930s, it has a double garage, with a twist – one for an automobile and one for the airplane that “World’s Fair optimists assumed every future family would own …”

One can only imagine how this garage has played out of time – rumpus room, game room, massive mud room, cluttered workshop where grandpa used to build boats in bottles, and now the place where mom and dad surf the internet when the other isn’t looking.

The House of Tomorrow held out a vision of the future at odds with much of what was going on around it. A few years earlier, World War I gave people a glimpse of the horror to be wrought by chemical warfare and bombs. In 1933, faith in individual action and the capitalist economy was well under seige. On February 27 of that year, Hitler burned the Reichstag and The Third Reich began. World War II, with its multiple Holocausts of genocide, firebombing, and nuclear warfare would be soon upon us.

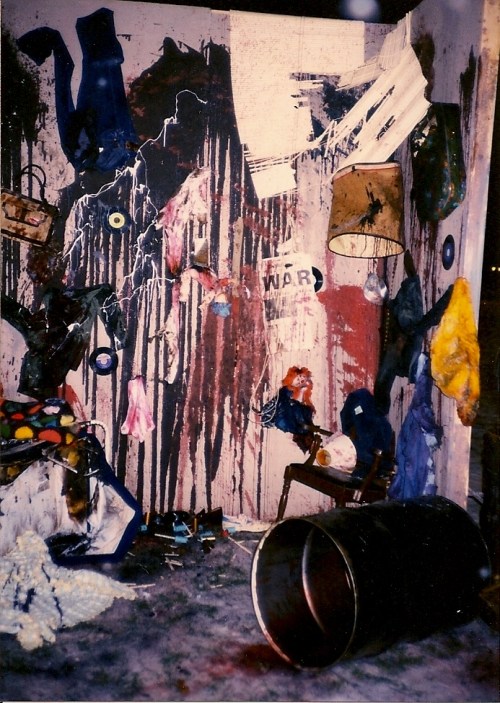

The House of Tomorrow, 1933, Berlin version

Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (published in 1973) portayed this entire destructive arc of the twentieth century. Science fuelled a spiral of violence, which unleashed and unbound human emotions both zany and horrific. Pynchon captured this most vividly in Brigadier Pudding’s humiliation scene, a Pavlovian experiment in the malleability/perfectibility of mankind that was a living annihilation at the border between the past and our future in which Pudding relived and relieved himself of the filth of Ypres and Passechendaele over and over again. The ritual became the center of his being.

Still, annihilation and holocaust were not the only ideas on the table. The playfulness of Pynchon’s novel and its main character, Tyrone Slothrop, held out the competing narratives of innocence and technologial redemption, impulses ironically (and perhaps hypocritcally) present in Robert Moses’s 1964 New York World’s Fair. This was the year of my birth and the year in which Stanley Kubrik gave us Dr. Strangelove. At the Fair, GM’s “Tomorrow Land” provided a delightful tour of the wonders yet to be bestowed on us by reinforced concrete, steel, and plastic. Tomorrow Land was a glimpse into the world that could be, minus the evils of nuclear war, poverty, and exploitation.

At the Fair’s Pepsi Pavilion, “Children of the World” used mechanized dolls and music to showcase a world of hope and diversity. This became Disney’s “It’s a Small World,” leading to the installation of its relentlessly saccharine theme song in the minds of millions of people every year, some of whom must wish that Slim Pickins would ride a missile into Orlando and put an end to the little dolls and gadgets just so they could get that song out of their heads.

The world we inherited in the Reagan years was reeling between the Jetsons and Dr. Strangelove as Paul Westerberg wrote “we’ll inherit the earth, but we don’t want it.” If we were finally, really going to do it, to blow it up, I’d at least try to spend my last years thinking of other things.

In 1981, I bought a TRS-80, Model III. I was 17 and had saved up the money from my job at the pizza parlor down the street. I read Alvin Toffler’s The Third Wave and John Nesbitt’s Megatrends. A future of progress was much more appealing future than the one forecast by the “Doomsday Clock” on the cover of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Such was the future according to Generation X, as we stumbled between slackerism and technoredemption.

In 1989, I remember being in my kitchen, washing dishes and listening to NPR when they announced that people had climbed over the Berlin Wall and were taking it apart. In my own mind, I replaced The Day After with Blondie and hummed “Atomic” over and over again as I felt relief wash over me.

Then in the mid-1990s, Newt Gingrich started invoking Alvin Toffler at every opportunity. 1984 and Y2K came and went with neither Orwellian nor apocalyptic futures taking hold. The most prescient glimpse of the future provided in my entire lifetime was not Space 1999 but Prince’s 1999, which accurately forecast exactly what I, and countless others around the world, were doing in 1999. Whatever the future would be, it would be weird, and once Tim Berners Lee put the World Wide Web up, Gen X went online and, as if following Hunter S. Thompson’s consultation to our parents, we went pro.

Technoredemption provided a kind of cure-all for anxiety about the future. Today it feeds the relentlessly positive assessments of Twitter’s contribution to revolution and freedom around the world. Yet the same technology can bring us back to Huxley or Orwell, and we know it. Evgeny Morozov writes that even as “activists and NGOs are turning to crowdsourcing to analyze data, map human rights violations, scrutinize the voting records of their MPs, and even track illegal logging in the Amazon”, ” governments are also relying on crowdsourcing to identify dissenters and muzzle free speech.”

Technoredemption remains as much a promise now as it was in 1776, 1933, 1964, or 1989. Rousseau’s famous line from the opening of On the Social Contract – “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains” – strikes me as quite true today, in the same sense that Rousseau meant it, and with the same consequences.

Notes and Credits

The photograph of the House of Tomorrow, Indiana version, was found on Wikipedia, in the commons at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:571531cv.jpg. The House of Tomorrow, Berlin version, is in the Wikimedia commons at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Reichstagsbrand.jpg.

We didn’t need nuclear bombs alone to create armageddons of pain and horror. Madhukar Shukla writes “The Firebombing of Tokyo was as devasting as the nuclear, Hidden in the history of that time, is an unnoticed footnote – the ‘Tokyo Fire-Bombing,’ which the Western press would not touch, and the Japanese survivors would not like to dwell upon [was an] event which happened months before the atom-bombs and with far more lethal consequences.” Shukla’s blog is called “Alternative Perspective” and his homepage is here.

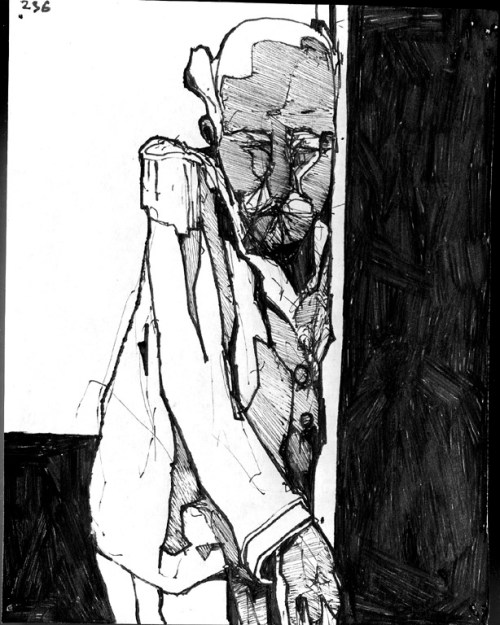

The illustration of Brig. Pudding is by Zak Smith, from his work Pictures Showing What Happens on Each Page of Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. Much thanks to Zak for granting me permission to use the image. The series of illustrations was featured in the 2004 Whitney Biennial (agh, just before I arrived in New York!) and is now part of the permanent collection at the Walker in Minneapolis. In the episode referenced above, Brig. Pudding must undergo a scatological humiliation scene with Domina Nocturna as part of his atonement for his role in Ypres and Passechendaele, a scene occupying pp. 232-36 of the book (Viking Press, 1973). Click on the image and you will be taken to a website featuring all of the illustrations.

Among Pynchon’s themes we count the Europeans’ damning of the world to endure the repetitive future of their own racist, colonial past, which sits perversely at the heart of American innocence and condemns America (white America, especially) to this struggle between technoredemption, dystopia, and annihilation. Like Rousseau, Pynchon sees the chains that reason has placed on mankind. He continues to explore that theme in his writing, with impressive intensity in Mason and Dixon, in which the two famous astronomers are contracted to create an artificial boundary between two artificial entites (Pennsylvania and Maryland) that have been imposed on something like a state of nature.

Pynchon’s new novel, Inherent Vice, goes into the territory of detective fiction and film noir, two of my favorite genres. I am giddy and cannot wait to read this book. Expect more posts related to TP.

On August 31, 2006, Douglas Coupland posted a wonderfully ironic vision of the future as past and present on his New York Times blog. At that point he boldly foresaw the Kindle-future, as he predicted that books will “cease to exist” and become “extinct.” Looking at his old novels and thinking of insects, he began to think about how wasps made paper from wood, and then he used his own mouth to pulp his novels and make nests from them. The resulting photos are quite beautiful, and the blog posting shows what Generation X looks like as a nest.

The photograph of the TRS-80 Model III comes from Stan Veit’s website, PC-History, based on his famous book, Stan Veit’s History of the Personal Computer.

I learned about Evgeny Morozov’s blog post in a Tweet from Cause Global’s Marcia Stepanek.

The ice age is coming, the sun’s zooming in

Engines stop running, the wheat is growing thin

A nuclear error, but I have no fear

Cause London is drowning and I, I live by the river